A synthetic vision system (SVS) is a computer-mediated reality system for aerial vehicles, that uses 3D to provide pilots with clear and intuitive means of understanding their flying environment.

Synthetic vision is also a generic term, which may pertain to computer vision systems using artificial intelligence methods for visual learning, see 'Synthetic Vision using Volume Learning and Visual DNA'.

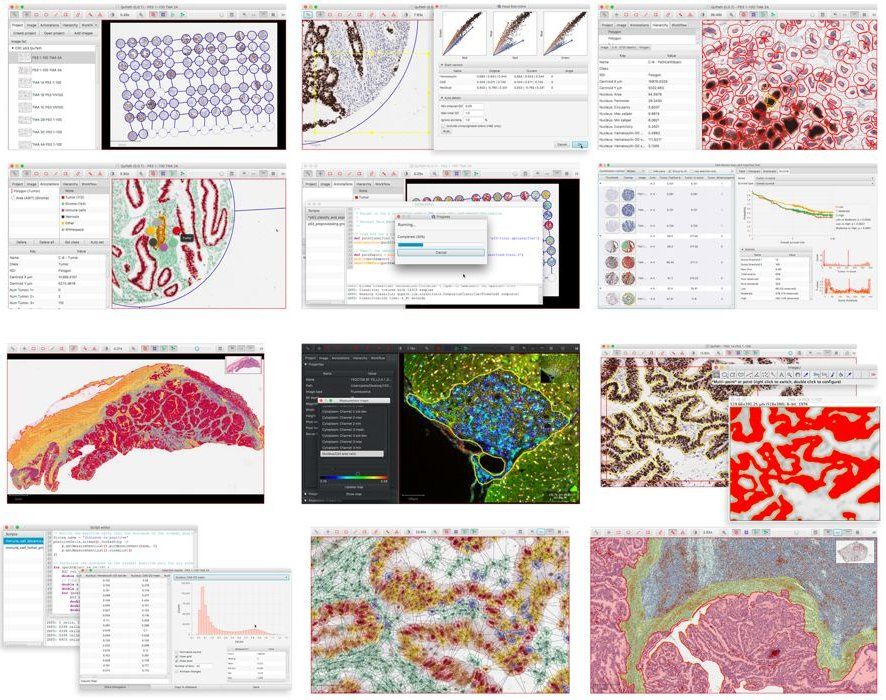

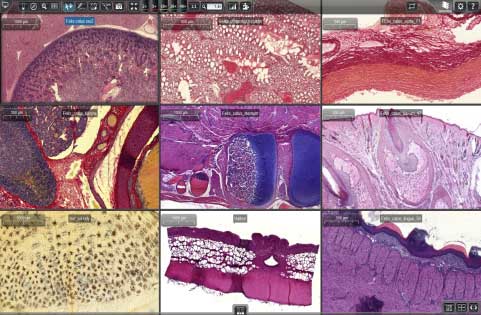

Join the thousands who use our freely downloadable ImageScope viewing software—experience rapid access to crisp, true-color digital slide images to which you can adjust magnification, pan and zoom, compare different stains, annotate areas of interest, perform image analysis, and more. VIA Mobile360 SVS utilizes VIA Multi-Stitch technology to seamlessly combine multiple camera streams creating an encompassing real-time spherical view of a vehicle's surroundings, providing the most effective solution for driver monitoring, safety, and vehicle tracking. A typical SVS application uses a set of databases stored on board the aircraft, an image generator computer, and a display. Navigation solution is obtained through the use of GPS and inertial reference systems. Highway In The Sky (HITS), or Path-In-The-Sky, is often used to depict the projected path of the aircraft in perspective view.

Functionality[edit]

Synthetic vision provides situational awareness to the operators by using terrain, obstacle, geo-political, hydrological and other databases. A typical SVS application uses a set of databases stored on board the aircraft, an image generator computer, and a display. Navigation solution is obtained through the use of GPS and inertial reference systems.

Highway In The Sky (HITS), or Path-In-The-Sky, is often used to depict the projected path of the aircraft in perspective view. Pilots acquire instantaneous understanding of the current as well as the future state of the aircraft with respect to the terrain, towers, buildings and other environment features.

History[edit]

A forerunner to such systems existed in the 1960s, with the debut into U.S. Navy service of the Grumman A-6 Intruder carrier-based medium-attack aircraft. Designed with a side-by-side seating arrangement for the crew, the Intruder featured an advanced navigation/attack system, called the Digital Integrated Attack and Navigation Equipment (DIANE), which linked the aircraft's radar, navigation and air data systems to a digital computer known as the AN/ASQ-61. Information from DIANE was displayed to both the Pilot and Bombardier/Navigator (BN) through cathode ray tube display screens. In particular, one of those screens, the AN/AVA-1 Vertical Display Indicator (VDI), showed the pilot a synthetic view of the world in front of the aircraft and, in Search Radar Terrain Clearance mode (SRTC), depicted the terrain detected by the radar, which was then displayed as coded lines that represented preset range increments. Called 'Contact Analog', this technology allowed the A-6 to be flown at night, in all weather conditions, at low altitude, and through rugged or mountainous terrain without the need for any visual references.[1]

Synthetic vision was developed by NASA and the U.S. Air Force in the late 1970s[2] and 1980s in support of advanced cockpit research, and in 1990s as part of the Aviation Safety Program. Development of the High Speed Civil Transport fueled NASA research in the 1980s and 1990s. In the early 1980s, the USAF recognized the need to improve cockpit situation awareness to support piloting ever more complex aircraft, and pursued SVS (also called pictorial format avionics) as an integrating technology for both manned and remotely piloted systems.[3]

Simulations and remotely piloted vehicles[edit]

In 1980 the FS1 Flight Simulator by Bruce Artwick for the Apple II microcomputer introduced recreational uses of synthetic vision.[4]

NASA used synthetic vision for remotely piloted vehicles (RPVs), such as the High Maneuvability Aerial Testbed or HiMAT.[5] According to the report by NASA, the aircraft was flown by a pilot in a remote cockpit, and control signals up-linked from the flight controls in the remote cockpit on the ground to the aircraft, and aircraft telemetry downlinked to the remote cockpit displays (see photo). The remote cockpit could be configured with either nose camera video or with a 3D synthetic vision display. SV was also used for simulations of the HiMAT. Sarrafian reports that the test pilots found the visual display to be comparable to output of camera on board the RPV.[5]

The 1986 RC Aerochopper simulation by Ambrosia Microcomputer Products, Inc. used synthetic vision to aid aspiring RC aircraft pilots in learning to fly. The system included joystick flight controls which would connect to an Amiga computer and display.[6] The software included a three-dimensional terrain database for the ground as well as some man-made objects. This database was basic, representing the terrain with relatively small numbers of polygons by today's standards. The program simulated the dynamic three-dimensional position and attitude of the aircraft using the terrain database to create a projected 3D perspective display. The realism of this RPV pilot training display was enhanced by allowing the user to adjust the simulated control system delays and other parameters.

Similar research continued in the U.S. military services, and at Universities around the world. In 1995-1996, North Carolina State University flew a 17.5% scale F-18 RPV using Microsoft Flight Simulator to create the three-dimensional projected terrain environment.[7]

Svs Viewer Online

In flight[edit]

In 2005 a synthetic vision system was installed on a Gulfstream V test aircraft as part of NASA's 'Turning Goals Into Reality' program.[8] Much of the experience gained during that program led directly to the introduction of certified SVS on future aircraft. NASA initiated industry involvement in early 2000 with major avionics manufacturers.

Eric Theunissen, a researcher at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, contributed to the development of SVS technology.[9]

At the end of 2007 and early 2008, the FAA certified the Gulfstream Synthetic Vision-Primary flight display (SV-PFD) system for the G350/G450 and G500/G550 business jet aircraft, displaying 3D color terrain images from the HoneywellEGPWS data overlaid with the PFD symbology.[10]It replaces the traditional blue-over-brown artificial horizon.

In 2017, Avidyne Corporation certified Synthetic Vision capability for its air navigation avionics.[11]Other glass cockpit systems such as the Garmin G1000 and the Rockwell Collins Pro Line Fusion offer synthetic terrain.

Lower-cost, non-certified avionics offer synthetic vision like apps available for Android or iPad tablet computers from ForeFlight,[12] Garmin,[13] or Hilton Software[14]

Regulations and standards[edit]

- 'RTCA DO-315B'. IEEE. 2011-06-21. Minimum aviation system performance standards for Enhanced Vision Systems, Synthetic Vision Systems, Combined Vision Systems and Enhanced Flight Vision Systems.

- 'ED-179B - MASP for Enhanced Vision Systems and Synthetic Vision Systems and Combined Vision Systems and Enhanced Flight Vision Systems'. EuroCAE. September 2011.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Andrews, Hal. 'Life of the Intruder'. Naval Aviation News, Volume 79, No. 6, September-October 1997, pp 8-16.Cite magazine requires

|magazine=(help) - ^Knox; et al. (October 1977). 'Description of Path-In-The-Sky Contact Analog Piloting Display'(PDF). Technical Memorandum 74057. NASA.

- ^Way; et al. (May 1984). 'Pictorial Format Display Evaluation'(PDF). AFWAL-TR-34-3036. USAF.

- ^Jos Grupping (2001). 'Introduction'. Flight Simulator History.[self-published source?]

- ^ abSarrafian, S (August 1984). 'Simulator Evaluation of a Remotely Piloted Vehicle Lateral Landing Task Using a Visual Display'(PDF). Technical Memorandum 85903. NASA. doi:10.2514/6.1984-2095.

- ^Stern, D: 'RC Aerochopper Owners Manual', Ambrosia Microcomputer Products, Inc., 1986

- ^'Flight Research (The F18 Project)'. North Carolina State University. Archived from the original on 2008-01-10.

- ^'Turning Goals into Reality 2005 Award Winners'. NASA Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate.

- ^Theunissen; et al. (August 2005). 'Guidance, Situation Awareness and Integrity Monitoring with an SVS+EVS'. AIAA GNC Conference Proceedings. doi:10.2514/6.2005-6441. ISBN978-1-62410-056-7.

- ^'Gulfstream scores double first as federal aviation administration certifies EVS II and synthetic vision primary flight display' (Press release). Gulfstream. January 28, 2008.

- ^'Avidyne certifies synthetic vision for FMS line'. General Aviation News. 2017-03-13.

- ^'Global synthetic vision'. ForeFlight.

- ^'Garmin Pilot App Adds 3-D Synthetic Vision Capability' (Press release). Garmin. February 20, 2014.

- ^'Hilton Software'.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Synthetic vision system. |

- 'Synthetic Vision Would Give Pilots Clear Skies All the Time'. NASA. 2004-11-21.

- Stephen Pope (June 2006). 'The promise of synthetic vision: turning ideas into (virtual) reality'(PDF). AIN online.

Please note: Adobe discontinued support for Adobe SVG Viewer on January 1, 2009. Please read Adobe discontinued SVG Viewer for more information. If you've been directed to download the SVG Viewer, it's an old message. You can open most SVG files in any modern browser. Before downloading the SVG Viewer, try opening the files in your web browser. |

Download Adobe® SVG Viewer 3 to view Scalable Vector Graphics in browsers that do not provide SVG, such as browsers from the early days of the millennium.

Adobe SVG Viewer 3.03

Version 3.03 of Adobe SVG Viewer is an update provided by Adobe to fix a potential secuirty risk on Windows® computers. In addition, the ActiveX control has been signed in order to allow users to avoid the ActiveX security warning introduced with Windows XP Security Pack 2.

Adobe SVG Viewer 3.03 addresses a potential security risk in the ActiveX control whereby a malicious web page could determine whether or not a file with a particular name exists on the user's computer. The contents of the file could not be viewed via this vulnerability, and directory listings could not be obtained. Adobe is not aware of any malicious exploit of this potential security risk, but we are grateful to Hyperdose Security for bringing this potential security risk to our attention. Adobe SVG Viewer 3.03 also includes the fixes provided in Adobe SVG Viewer 3.02.

Adobe SVG Viewer 3.02

Version 3.02 of Adobe SVG Viewer is an update provided by Adobe to fix a potential secuirty risk on Windows computers, and to fix a bug in the installer which prevented installation on some Windows XP systems.

Adobe SVG Viewer 3.02 addresses a potential security risk in libpng described by CERT vulnerability 388984. Please see the CERT vulnerability note for details. Adobe SVG Viewer 3.02 also includes the fixes provided in Adobe SVG Viewer 3.01.

Adobe SVG Viewer 3.01

Version 3.01 of Adobe SVG Viewer is an update provided by Adobe to fix potential security risks on Windows computers.

Adobe SVG Viewer 3.01 addresses one potential security risk by disabling SVG scripts if you disable ActiveScripting in Internet Explorer. This security risk only affects customers who browse the Web on Windows computers in Internet Explorer with ActiveScripting disabled. By default, ActiveScripting is enabled, so most users are not currently at risk. Because of the way that the HTML OBJECT tag is implemented in Internet Explorer, Adobe SVG Viewer 3.01 cannot determine the URL of a file embedded with the OBJECT tag. The URL is required to determine the security zone, which is required to determine the state of the ActiveScripting setting. Therefore, to fail safe against this potential security flaw Adobe SVG Viewer 3.01 always disables scripting when it determines that the SVG file is embedded using the OBJECT tag. When authoring in SVG, Adobe recommends that you not use the OBJECT tag and instead use the EMBED tag when embedding SVG in HTML pages.

Synthetic vision was developed by NASA and the U.S. Air Force in the late 1970s[2] and 1980s in support of advanced cockpit research, and in 1990s as part of the Aviation Safety Program. Development of the High Speed Civil Transport fueled NASA research in the 1980s and 1990s. In the early 1980s, the USAF recognized the need to improve cockpit situation awareness to support piloting ever more complex aircraft, and pursued SVS (also called pictorial format avionics) as an integrating technology for both manned and remotely piloted systems.[3]

Simulations and remotely piloted vehicles[edit]

In 1980 the FS1 Flight Simulator by Bruce Artwick for the Apple II microcomputer introduced recreational uses of synthetic vision.[4]

NASA used synthetic vision for remotely piloted vehicles (RPVs), such as the High Maneuvability Aerial Testbed or HiMAT.[5] According to the report by NASA, the aircraft was flown by a pilot in a remote cockpit, and control signals up-linked from the flight controls in the remote cockpit on the ground to the aircraft, and aircraft telemetry downlinked to the remote cockpit displays (see photo). The remote cockpit could be configured with either nose camera video or with a 3D synthetic vision display. SV was also used for simulations of the HiMAT. Sarrafian reports that the test pilots found the visual display to be comparable to output of camera on board the RPV.[5]

The 1986 RC Aerochopper simulation by Ambrosia Microcomputer Products, Inc. used synthetic vision to aid aspiring RC aircraft pilots in learning to fly. The system included joystick flight controls which would connect to an Amiga computer and display.[6] The software included a three-dimensional terrain database for the ground as well as some man-made objects. This database was basic, representing the terrain with relatively small numbers of polygons by today's standards. The program simulated the dynamic three-dimensional position and attitude of the aircraft using the terrain database to create a projected 3D perspective display. The realism of this RPV pilot training display was enhanced by allowing the user to adjust the simulated control system delays and other parameters.

Similar research continued in the U.S. military services, and at Universities around the world. In 1995-1996, North Carolina State University flew a 17.5% scale F-18 RPV using Microsoft Flight Simulator to create the three-dimensional projected terrain environment.[7]

Svs Viewer Online

In flight[edit]

In 2005 a synthetic vision system was installed on a Gulfstream V test aircraft as part of NASA's 'Turning Goals Into Reality' program.[8] Much of the experience gained during that program led directly to the introduction of certified SVS on future aircraft. NASA initiated industry involvement in early 2000 with major avionics manufacturers.

Eric Theunissen, a researcher at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, contributed to the development of SVS technology.[9]

At the end of 2007 and early 2008, the FAA certified the Gulfstream Synthetic Vision-Primary flight display (SV-PFD) system for the G350/G450 and G500/G550 business jet aircraft, displaying 3D color terrain images from the HoneywellEGPWS data overlaid with the PFD symbology.[10]It replaces the traditional blue-over-brown artificial horizon.

In 2017, Avidyne Corporation certified Synthetic Vision capability for its air navigation avionics.[11]Other glass cockpit systems such as the Garmin G1000 and the Rockwell Collins Pro Line Fusion offer synthetic terrain.

Lower-cost, non-certified avionics offer synthetic vision like apps available for Android or iPad tablet computers from ForeFlight,[12] Garmin,[13] or Hilton Software[14]

Regulations and standards[edit]

- 'RTCA DO-315B'. IEEE. 2011-06-21. Minimum aviation system performance standards for Enhanced Vision Systems, Synthetic Vision Systems, Combined Vision Systems and Enhanced Flight Vision Systems.

- 'ED-179B - MASP for Enhanced Vision Systems and Synthetic Vision Systems and Combined Vision Systems and Enhanced Flight Vision Systems'. EuroCAE. September 2011.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Andrews, Hal. 'Life of the Intruder'. Naval Aviation News, Volume 79, No. 6, September-October 1997, pp 8-16.Cite magazine requires

|magazine=(help) - ^Knox; et al. (October 1977). 'Description of Path-In-The-Sky Contact Analog Piloting Display'(PDF). Technical Memorandum 74057. NASA.

- ^Way; et al. (May 1984). 'Pictorial Format Display Evaluation'(PDF). AFWAL-TR-34-3036. USAF.

- ^Jos Grupping (2001). 'Introduction'. Flight Simulator History.[self-published source?]

- ^ abSarrafian, S (August 1984). 'Simulator Evaluation of a Remotely Piloted Vehicle Lateral Landing Task Using a Visual Display'(PDF). Technical Memorandum 85903. NASA. doi:10.2514/6.1984-2095.

- ^Stern, D: 'RC Aerochopper Owners Manual', Ambrosia Microcomputer Products, Inc., 1986

- ^'Flight Research (The F18 Project)'. North Carolina State University. Archived from the original on 2008-01-10.

- ^'Turning Goals into Reality 2005 Award Winners'. NASA Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate.

- ^Theunissen; et al. (August 2005). 'Guidance, Situation Awareness and Integrity Monitoring with an SVS+EVS'. AIAA GNC Conference Proceedings. doi:10.2514/6.2005-6441. ISBN978-1-62410-056-7.

- ^'Gulfstream scores double first as federal aviation administration certifies EVS II and synthetic vision primary flight display' (Press release). Gulfstream. January 28, 2008.

- ^'Avidyne certifies synthetic vision for FMS line'. General Aviation News. 2017-03-13.

- ^'Global synthetic vision'. ForeFlight.

- ^'Garmin Pilot App Adds 3-D Synthetic Vision Capability' (Press release). Garmin. February 20, 2014.

- ^'Hilton Software'.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Synthetic vision system. |

- 'Synthetic Vision Would Give Pilots Clear Skies All the Time'. NASA. 2004-11-21.

- Stephen Pope (June 2006). 'The promise of synthetic vision: turning ideas into (virtual) reality'(PDF). AIN online.

Please note: Adobe discontinued support for Adobe SVG Viewer on January 1, 2009. Please read Adobe discontinued SVG Viewer for more information. If you've been directed to download the SVG Viewer, it's an old message. You can open most SVG files in any modern browser. Before downloading the SVG Viewer, try opening the files in your web browser. |

Download Adobe® SVG Viewer 3 to view Scalable Vector Graphics in browsers that do not provide SVG, such as browsers from the early days of the millennium.

Adobe SVG Viewer 3.03

Version 3.03 of Adobe SVG Viewer is an update provided by Adobe to fix a potential secuirty risk on Windows® computers. In addition, the ActiveX control has been signed in order to allow users to avoid the ActiveX security warning introduced with Windows XP Security Pack 2.

Adobe SVG Viewer 3.03 addresses a potential security risk in the ActiveX control whereby a malicious web page could determine whether or not a file with a particular name exists on the user's computer. The contents of the file could not be viewed via this vulnerability, and directory listings could not be obtained. Adobe is not aware of any malicious exploit of this potential security risk, but we are grateful to Hyperdose Security for bringing this potential security risk to our attention. Adobe SVG Viewer 3.03 also includes the fixes provided in Adobe SVG Viewer 3.02.

Adobe SVG Viewer 3.02

Version 3.02 of Adobe SVG Viewer is an update provided by Adobe to fix a potential secuirty risk on Windows computers, and to fix a bug in the installer which prevented installation on some Windows XP systems.

Adobe SVG Viewer 3.02 addresses a potential security risk in libpng described by CERT vulnerability 388984. Please see the CERT vulnerability note for details. Adobe SVG Viewer 3.02 also includes the fixes provided in Adobe SVG Viewer 3.01.

Adobe SVG Viewer 3.01

Version 3.01 of Adobe SVG Viewer is an update provided by Adobe to fix potential security risks on Windows computers.

Adobe SVG Viewer 3.01 addresses one potential security risk by disabling SVG scripts if you disable ActiveScripting in Internet Explorer. This security risk only affects customers who browse the Web on Windows computers in Internet Explorer with ActiveScripting disabled. By default, ActiveScripting is enabled, so most users are not currently at risk. Because of the way that the HTML OBJECT tag is implemented in Internet Explorer, Adobe SVG Viewer 3.01 cannot determine the URL of a file embedded with the OBJECT tag. The URL is required to determine the security zone, which is required to determine the state of the ActiveScripting setting. Therefore, to fail safe against this potential security flaw Adobe SVG Viewer 3.01 always disables scripting when it determines that the SVG file is embedded using the OBJECT tag. When authoring in SVG, Adobe recommends that you not use the OBJECT tag and instead use the EMBED tag when embedding SVG in HTML pages.

Adobe SVG Viewer 3.01 also includes a fix for a potential security risk involving the JavaScript alert call when used in conjunction with JavaScript executing in another thread. It was possible for an SVG document to pop up an alert dialog while another script in the HTML document changed the location of the window to a private domain. When the original script regained control it would have been able to access private domains and potentially send protected information to a remote machine.

Adobe is not aware of any malicious exploits of these potential security risks, but we are grateful to GreyMagic Security Research for bringing these potential security risks to our attention.

Downloads

By downloading software from the Adobe Web site you agree to the terms of our license agreement. Please read it before downloading.

Installing Adobe SVG Viewer

- Double-click the downl oaded installer.

- Follow the on-screen instructions.

- If you are not using Internet Exporer for Windows, then you will need to restart your browser before viewing SVG.

Viewers

| Language | Operating system | Version | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| RedHat Linux 7.1–9e | 3.01 beta 3 | 12/2003 | |

| Solaris 8 | 3.0 beta 1 | 11/2001 | |

| 繁体字 | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| 繁體字 | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Česká republika | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Dansk | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Deutsch | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Ελληνικα | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Español | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Français | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Italiano | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| 日本 | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| 한국 | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Magyar | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Nederlands | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Norsk | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Polski | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Português | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Suomeksi | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Svenska | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Türkçe | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

Add-on support for ICC colors

.svs File Viewer

| Language | Operating system | Version | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| 繁体字 | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| 繁體字 | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Česká republika | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Dansk | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Deutsch | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Ελληνικα | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Español | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Français | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Italiano | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| 日本 | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| 한국 | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Magyar | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Nederlands | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Norsk | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Polski | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Português | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Suomeksi | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Svenska | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |

| Mac 8.6–9.1 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Mac 10.1–10.4 | 3.0 | 11/2001 | |

| Türkçe | Win 98–XP | 3.03 | 04/2005 |